Design & Editing

internal war was finally over. Beethoven wrote his Ninth Symphony in a time when freedom was repressed in Europe. Music scholars have tried to put meaning to that symphony for years, without success. What they do know, and anyone who hears it knows, is it is one of the greatest pieces of music ever written. For me, it has always and still does elevate my soul to a higher place of hope, love, and freedom. Then there is Bach’s Partita for Keyboard no. 2 in D Minor. There is a happy, light, dancelike quality to this particular piece of music, and I was certainly feeling that when I met the boys as adults.

M

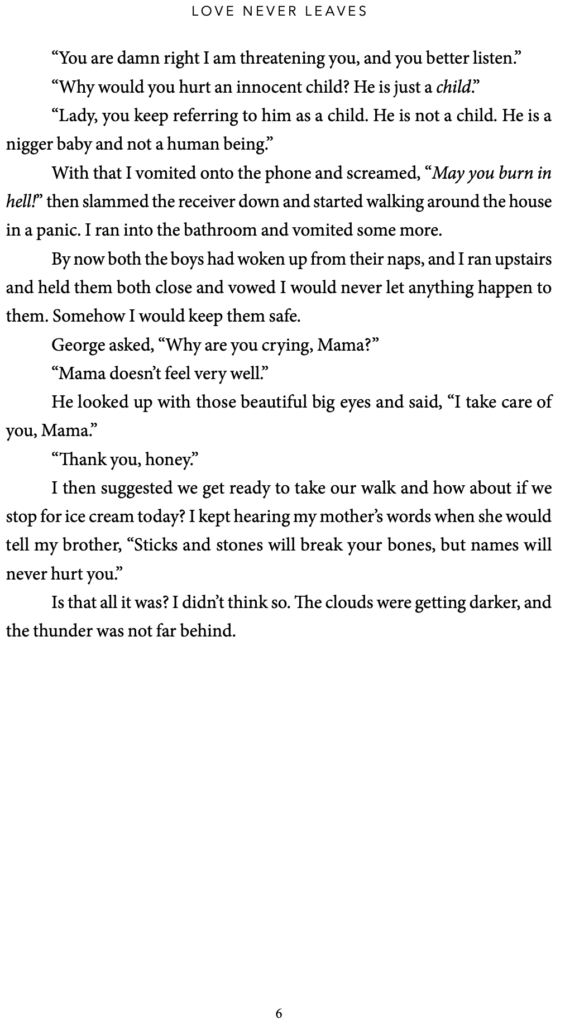

y son and I were invited to Deb and

Jack Blanchard’s home in Braintree, Massachusetts, one day in 2010. Deb is the birth mother of my cousin David, whom she put up for adoption, along with his brother, George, when they were preschoolers. Deb had received threats after returning with them to her predominantly white hometown following the breakdown of her first marriage. Dave and George (who is deceased) are/were biracial; Deb is white. She subsequently became an adoption activist and asked me, that day in Braintree, if I would help her write a how-to book about finding lost relatives.

I had been out of the publishing industry for a while and carelessly asked Deb what kind of writing she had done previously. She showed me something—a shopping list, a Christmas card perhaps—and I said OK. Deb then sent me a couple of “chapters,” which were about 300 words apiece. I knew then that I was in trouble.

I suggested that she tell her own story instead. To my surprise, she agreed. That began an 11-year project that resulted in Love Never Leaves (BookBaby, 2022), Deb’s memoir, which includes shorter pieces by people she met through her activism and one by George, who died shortly before publication.

Nothing about this summary so far would persuade anyone to read the book, I realize, but it’s an accurate account of the unpromising start of that project. It’s also misleading.

Shortly after my son and I moved to Massachusetts, in 2004, we received our first invitation to Deb and Jack’s house, and I was not pleased. I did not want to be trapped in an older couple’s living room for hours. Of course, we did enjoy ourselves that day, and after agreeing, six years later, to edit Deb’s book, I spent endless hours on the phone with her for the next decade, discussing writing, race and her past. Initially, she could recall little of that past, presumably because of the trauma she had endured, including being held out of a six-floor window after telling her first husband she was thinking of leaving him.

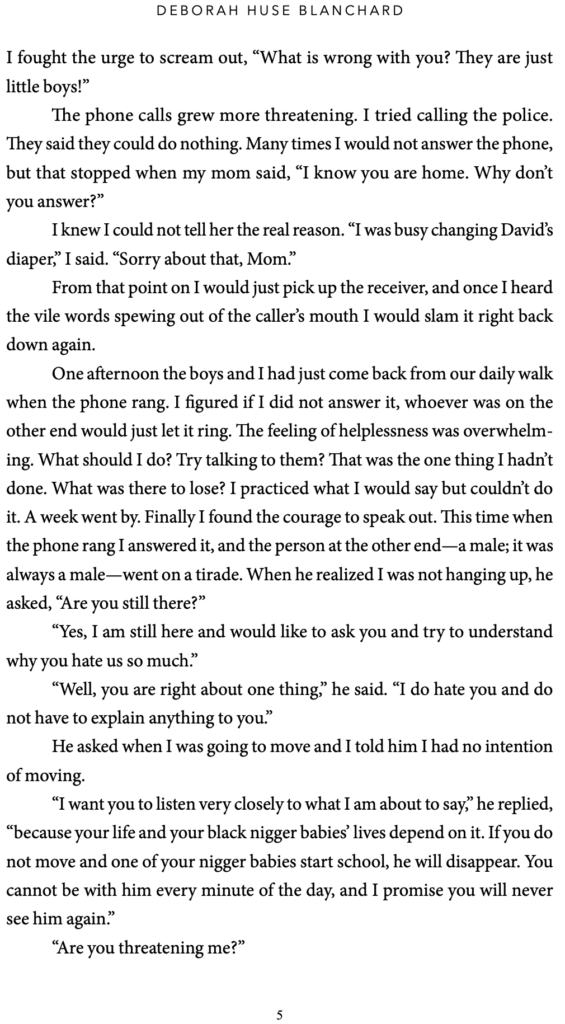

Deb is an avid reader, but her writing skills, naturally, were raw. The first full manuscript she sent me was filled with metaphors about her head exploding, her heart bursting and bad weather—over and over, the same turns of phrase for 170-plus pages. But she had more determination than any writer I have worked with. None have responded as patiently after being sent back for rewrite after rewrite. She was dead set on getting the book right, and ultimately she did.

I was proudest of her for the way she answered the big question any person who has been through a difficult situation will be asked: How did it feel?

Deb had been a naive young woman in 1949 when she arrived at the New England Conservatory of Music, where she met Dave and George’s dad. She cared about little beyond music. She was a singer, and her specialty was Lieder: German art songs.

In the early drafts of the book, she summarized her reaction to reconnecting with her sons, once they were grown, with the phrase “Words cannot describe…” We were in about the 10th round of edits before I decided it was time to tackle that cliché. Without complaint she went back to work and returned with the following:

Is it genius? Perhaps not, but it perfectly expresses who Deb is, and that is as much as an editor can ask of any memoirist.

I ended up designing the covers, partly because Deb did not understand that the sketches I had given her were just proposed concepts. Most books about adoption, she informed me, had some version of the mother-and-child-waving-goodbye approach that I suggested. We went back and forth on the concept, but in the end, it was a team effort, like nearly everything else about the book. I think that’s a key to success in any publishing venture.

I have been an editor (not copy editor) on about seven other books, with varying degrees of responsibility. I began copyediting my longtime colleague and friend Matt Birkbeck’s magazine articles 15 to 20 years ago and progressed to copyediting his books and then doing an edit on the last three, including The Life We Chose (William Morrow, 2023). I have also worked on another friend/colleague’s novel, plus a book on mentorship and two on the authors’ families. I am currently working on two more memoirs: one by a film and TV director who moved her family to India and another about an abusive childhood.

When Tchaikovsky wrote his “1812 Overture” in 1880, it was to celebrate the ending of the war against Napoleon, and when the crashing of the cymbals reaches its crescendo, it replicates the explosion of emotions I felt when I met the boys, as well as the sense that my

Love Never Leaves: A Memoir