Managing & Editing

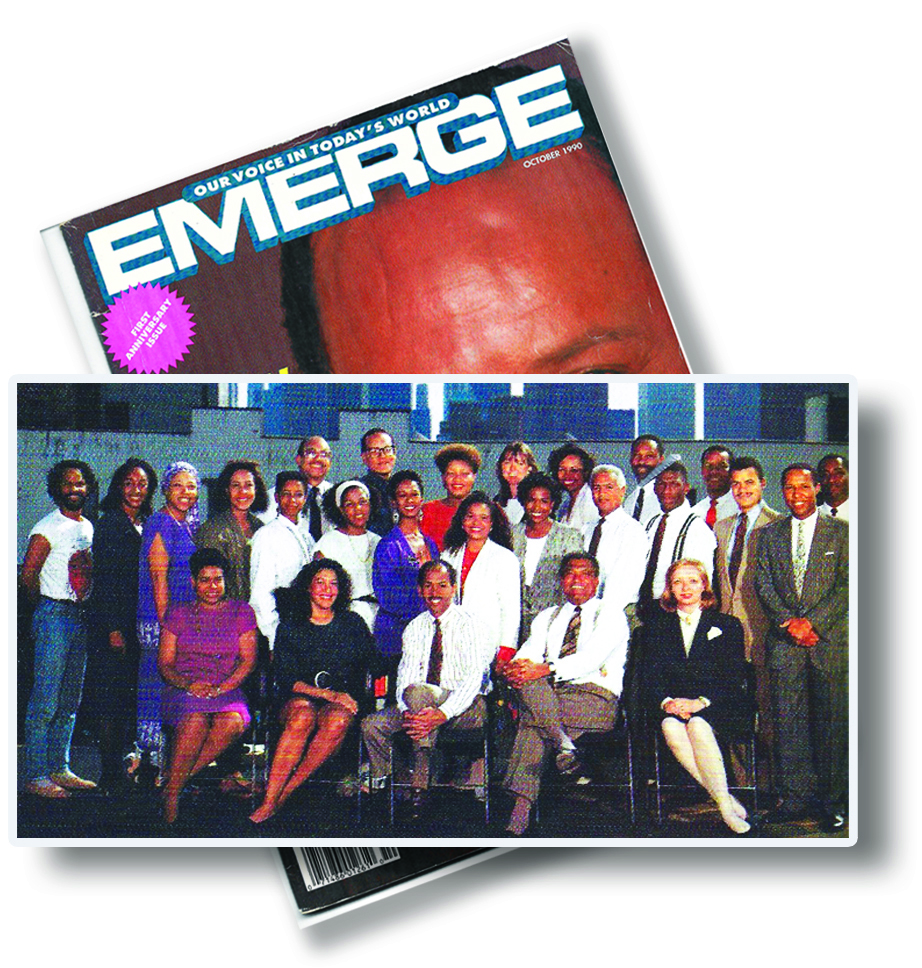

E

merge was a news magazine for African

Americans that lasted five tumultuous years under shifting ownership. It was originally backed by Time Inc., which relinquished its majority stake to avoid the implications of white ownership of black media. Most of the start-up staff came from Time Inc., however, which ensured a certain level of competence but not, as it turned out, comity.

I was hired as assistant managing editor as the staff was preparing the third issue. I was so thrilled that I radiated positivity, which came in handy in the months ahead.

Conflict abounded at the magazine generally, and shouting matches at the highest levels were not unheard of—nor unheard. When the managing editor left abruptly after a year, responsibility for closings was thrust onto my lap, an ominous turn of events since we closed two weeks late on average. The managing editor soon returned and I made a proposal: that we increase specialization, with the editor and managing editor handling content, while I focused on staff oversight.

The editorial staff included four junior editors, who often had little to do, while the managing editor and I edited 80 percent of the book.

The junior editors’ roles had initially been indistinguishable, and there was one who tended to get on the others’ nerves. Eventually I had enough of her myself and told the editor we needed to get rid of her.

“No!” he said sharply. “You go back in there and work with her.” I slunk out of his office and returned to my own, trying to figure out what to do. I concluded that the troublesome editor was more focused on details than the rest and was very self-assured. Those were qualities of a copy editor, I knew. Ironically, I ended up making her my assistant and she shone in that role. She became sort of my hatchet man in enforcing deadlines and did most of the copyediting. Altogether, that got my specialization plan off to a good start.

I also proposed that I train the other junior editors to carry more of the editing load, and we shaved three or four days off our late closings with each subsequent issue. Years later, I was up for the editorship of a recent start-up and it quickly became clear during the interview that what they really wanted was someone who could fire people. I don’t believe in firing, I told them, knowing it would sabotage my candidacy. Firing only pushes problems back while a new person learns the ropes and management learns about his or her shortcomings. We all have them. The key for any successful organization, I believe, is making maximum use of the assets you possess, not trading them in for the fool’s gold of new personnel.

And what happened ultimately at Emerge? When Rodney King was assaulted by a gang of cops, we overrode the deadline with the production editor absent. When she returned, she raised a stink, demanding that I overhaul my system and claiming my assistant was part of the problem. I resigned on the spot. A couple of years after that I hired my old assistant to proofread at Rolling Stone. When I asked her what kind of boss I had been she shrugged and said, “Eh, you were OK.”

From Emerge